The long-term efficacy of Brintellix® (vortioxetine) for working patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) [1]

MDD has a considerable impact in the workplace worldwide.2 Patients with MDD typically experience impaired functioning, particularly in their ability to work and their work productivity.3-7 In fact, compared to the general population, patients with MDD have shown increased absenteeism8 and reduced work productivity.9

To reduce the impact of MDD at work, current guidelines recommend long-term

treatment of at least six months after achieving symptomatic remission for patients with MDD who have responded to acute treatment.10,11

An analysis of the open-label AtWoRC (Assessment in Work productivity and the Relationship with Cognitive symptoms) study assessed long-term treatment outcomes in working patients with MDD treated with Brintellix® 10-20 mg/day over 52 weeks.†1

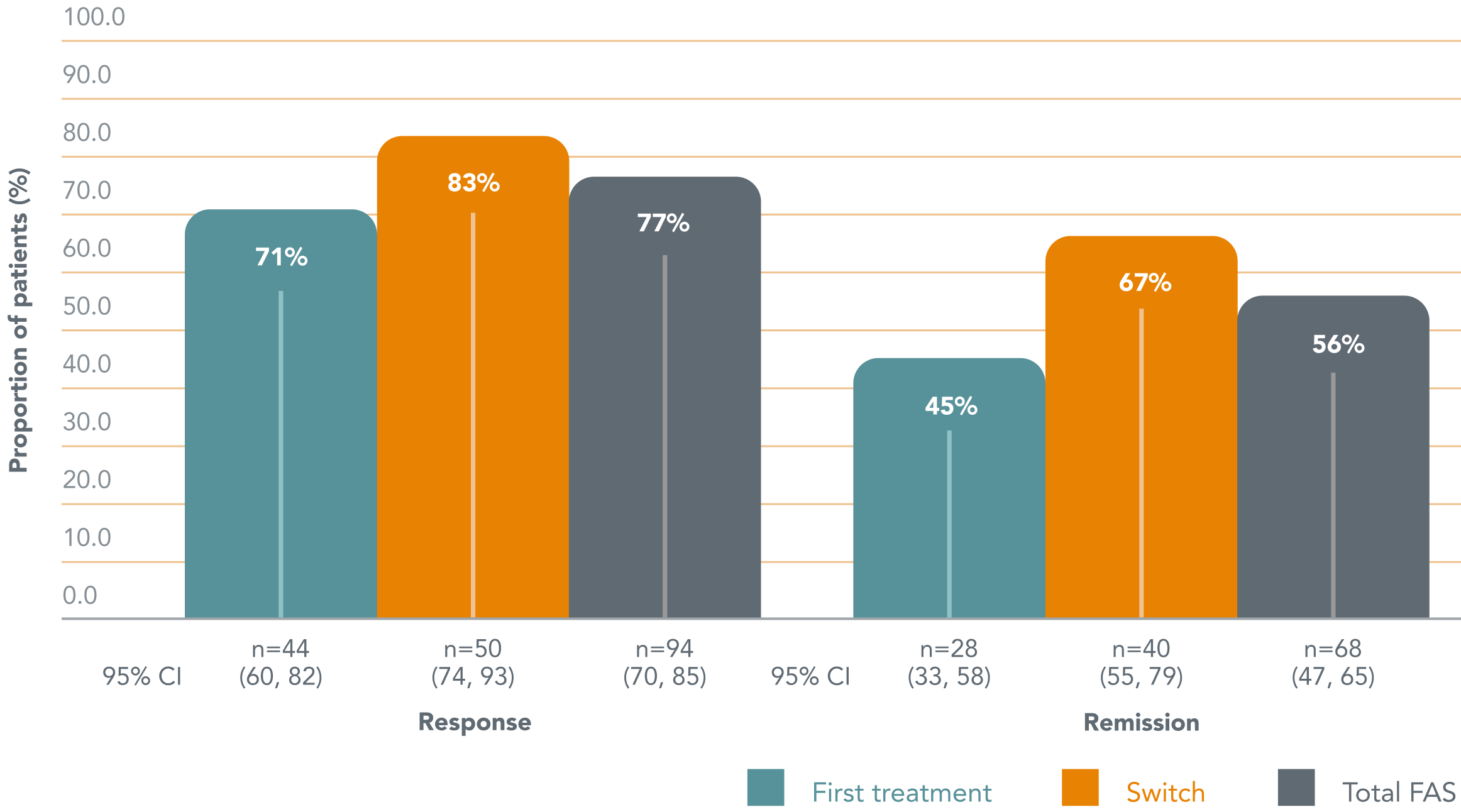

After 52 weeks of treatment with Brintellix® (10-20mg/day), 56% of employed patients achieved remission and 77% of patients achieved treatment response†1

Rates of treatment response and remission after 52 weeks of Brintellix® treatment†1

Adapted from: Chokka P et al. 2019.

Of those with a partial response to their prior treatment, 67% of patients achieved remission with Brintellix®†1 and 83% achieved treatment response.1

Cognitive symptoms (PDQ-D-20) and workplace functioning (WLQ) significantly improved§ for patients in this study, with a strong and highly significant correlation found between the two.¶1

Adapted from: Chokka P et al. 2019.

Of those with a partial response to their prior treatment, 67% of patients achieved remission with Brintellix®†1 and 83% achieved treatment response.1

Cognitive symptoms (PDQ-D-20) and workplace functioning (WLQ) significantly improved§ for patients in this study, with a strong and highly significant correlation found between the two.¶1

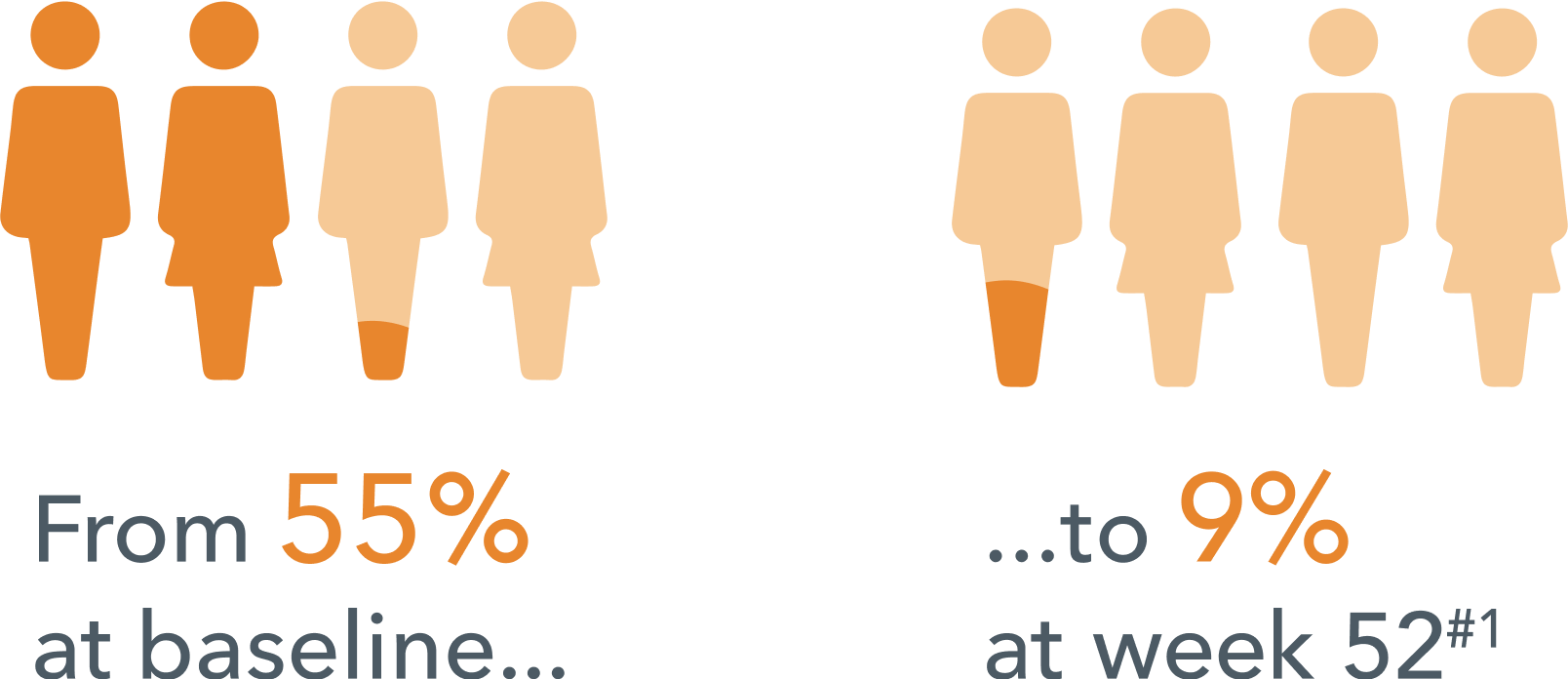

Fewer patients reported missed work days due to depression in the past 3 months #1

Fewer patients reported missed work days due to depression in the past 3 months #1

The study additionally found that improvements in depressive symptoms (as measured by QIDS-SR) seen in the short term were also sustained over the long term.§1

Overall, these results demonstrate the long-term benefits of Brintellix® treatment in working patients with MDD in clinical practice.1

Long term treatment with Brintellix® was generally well-tolerated and the most common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were nausea (29.2%), headache (11.9%), insomnia (9.1%), nasopharyngitis (6.8%), anxiety (6.4%), and dizziness (5.9%).1 Only few patients discontinued due to TEAEs (7.3%).1

The study additionally found that improvements in depressive symptoms (as measured by QIDS-SR) seen in the short term were also sustained over the long term.§1

Overall, these results demonstrate the long-term benefits of Brintellix® treatment in working patients with MDD in clinical practice.1

Long term treatment with Brintellix® was generally well-tolerated and the most common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were nausea (29.2%), headache (11.9%), insomnia (9.1%), nasopharyngitis (6.8%), anxiety (6.4%), and dizziness (5.9%).1 Only few patients discontinued due to TEAEs (7.3%).1

* Fictitious patient quote.

† Remission was defined as a QIDS-SR total score ≤5. Treatment response was defined as a change in QIDSSR of ≥50% from baseline. Patients were stratified according to whether Brintellix® was their first treatment for the current depressive episode or whether they were switching to Brintellix® due to a partial response to antidepressant treatment of the current episode.1

# Observed cases in the population.

§ Changes were assessed from baseline to week 12 (short-term) and week 52 (long-term), respectively. Change from baseline to week 52 in assessment scores in the full analysis set (observed cases), n=199; WLQ productivity loss -8.9, PDQ-D-20 -30.4, QIDS-SR -12.2; all changes are p<0.001 versus baseline.1

¶ A strong and highly significant correlation was seen between improvements in patient-rated cognitive symptoms (PDQ-D-20) and work productivity (WLQ) (study primary endpoint) at week 12 (r=0.606, p≤0.001) and week 52 (r=0.665, p≤0.001).1

Abbreviations:

AtWoRC, assessment in work productivity and the relationship with cognitive symptoms; MDD, major depressive disorder; PDQ-D-20, 20-item perceived deficits questionnaire-depression; QIDS-SR, quick inventory of depressive symptomatology – self-report; TEAE, treatment-emergeng adverse event; WLQ, work limitations questionnaire.

* Fictitious patient quote.

† Remission was defined as a QIDS-SR total score ≤5. Treatment response was defined as a change in QIDSSR of ≥50% from baseline. Patients were stratified according to whether Brintellix® was their first treatment for the current depressive episode or whether they were switching to Brintellix® due to a partial response to antidepressant treatment of the current episode.1

# Observed cases in the population.

§ Changes were assessed from baseline to week 12 (short-term) and week 52 (long-term), respectively. Change from baseline to week 52 in assessment scores in the full analysis set (observed cases), n=199; WLQ productivity loss -8.9, PDQ-D-20 -30.4, QIDS-SR -12.2; all changes are p<0.001 versus baseline.1

¶ A strong and highly significant correlation was seen between improvements in patient-rated cognitive symptoms (PDQ-D-20) and work productivity (WLQ) (study primary endpoint) at week 12 (r=0.606, p≤0.001) and week 52 (r=0.665, p≤0.001).1

Abbreviations:

AtWoRC, assessment in work productivity and the relationship with cognitive symptoms; MDD, major depressive disorder; PDQ-D-20, 20-item perceived deficits questionnaire-depression; QIDS-SR, quick inventory of depressive symptomatology – self-report; TEAE, treatment-emergeng adverse event; WLQ, work limitations questionnaire.