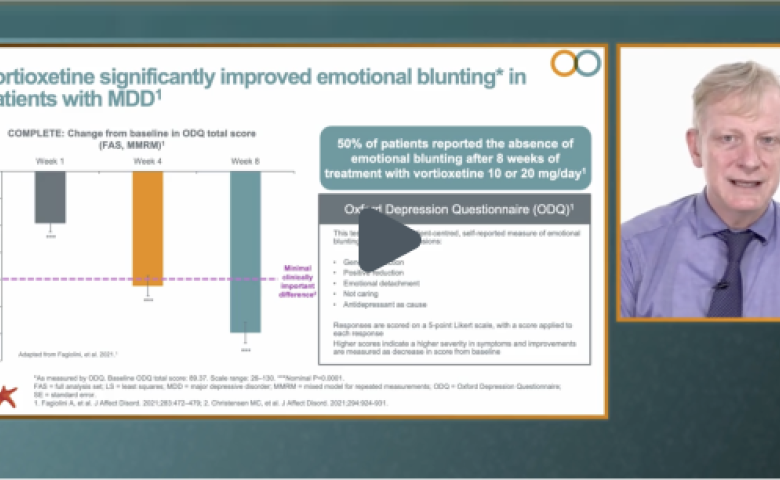

Brintellix® showed clinically meaningful reductions in emotional blunting† in patients with MDD with a partial response to previous SSRIs/SNRIs‡1,3

Brintellix® (vortioxetine) 10-20 mg/day) demonstrated a broad impact on emotional blunting† in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD).

The COMPLETE study is an interventional, 8-week, open-label, flexible-dose (10-20 mg/day) study of Brintellix® on emotional blunting (measured by the Oxford Depression Questionnaire2 , ODQ) in patients with MDD with a partial response to current treatment to previous SSRIs/SNRIs‡1. From week 1, Brintellix® significantly reduced all ODQ subdomains.1 Read the key findings on emotional blunting from this study below.

Mean change in ODQ total and domain scores from baseline#1

Adapted from: Fagiolini A et al. 2021.

#Baseline Section 1 and 2 score = 73.6 (scale range 20 100); baseline NC score = 18.2 (scale range 5–25); baseline PR score = 22.0 (scale range 5–25); baseline ED score = 14.7 (scale range 5–25); baseline GR score = 18.9 (scale range 5–25); baseline AC score = 15.7 (scale range 6–30).1

nominal p<0.05; **nominal p≤0.001; ***nominal p<0.0001

All patients included in this study reported substantial emotional blunting (ODQ≥50) at baseline, with an average ODQ total score of 89.4.1 After 8 weeks of treatment with Brintellix®, patients (N=143) improved by -29.8 points (p<0.0001) in ODQ total score.1 Significant improvements were seen across all ODQ subdomains, including not caring, emotional detachment, positive reduction and general reduction and antidepressant as cause, at weeks 1, 4 and 8. Brintellix® showed clinically meaningful¶ reductions in emotional blunting at week 4 and week 8.1,3

Adapted from: Fagiolini A et al. 2021.

#Baseline Section 1 and 2 score = 73.6 (scale range 20 100); baseline NC score = 18.2 (scale range 5–25); baseline PR score = 22.0 (scale range 5–25); baseline ED score = 14.7 (scale range 5–25); baseline GR score = 18.9 (scale range 5–25); baseline AC score = 15.7 (scale range 6–30).1

nominal p<0.05; **nominal p≤0.001; ***nominal p<0.0001

All patients included in this study reported substantial emotional blunting (ODQ≥50) at baseline, with an average ODQ total score of 89.4.1 After 8 weeks of treatment with Brintellix®, patients (N=143) improved by -29.8 points (p<0.0001) in ODQ total score.1 Significant improvements were seen across all ODQ subdomains, including not caring, emotional detachment, positive reduction and general reduction and antidepressant as cause, at weeks 1, 4 and 8. Brintellix® showed clinically meaningful¶ reductions in emotional blunting at week 4 and week 8.1,3

Overall depressive symptom resolution, measured with the MADRS total score, improved significantly from baseline to week 1 (mean change -3.3 points; p<0.0001) and continuously improved to week 8 (mean change from baseline -13.8 points; p<0.0001).1

The study confirmed the generally well-tolerated profile of Brintellix® as demonstrated in previous studies.4 The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs; reported by >5% of the study group) were nausea (20.7%), headache (8.0%), dizziness (6.7%), vomiting (6.7%) and diarrhoea (6.0%).1

Did you miss the the video with renowned international expert Professor Andrea Fagiolini explaining the COMPLETE study outcomes? Watch here.

Overall depressive symptom resolution, measured with the MADRS total score, improved significantly from baseline to week 1 (mean change -3.3 points; p<0.0001) and continuously improved to week 8 (mean change from baseline -13.8 points; p<0.0001).1

The study confirmed the generally well-tolerated profile of Brintellix® as demonstrated in previous studies.4 The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs; reported by >5% of the study group) were nausea (20.7%), headache (8.0%), dizziness (6.7%), vomiting (6.7%) and diarrhoea (6.0%).1

Did you miss the the video with renowned international expert Professor Andrea Fagiolini explaining the COMPLETE study outcomes? Watch here.

† As measured by ODQ, an effective self-report measure of the symptoms of emotional blunting in patients with depression.2

‡ Partial response defined by the investigators clinical judgement of symptom severity and type to an SSRI or SNRI monotherapy at approved doses for at least 6 weeks before the screening visit. Previous SSRIs included escitalopram, paroxetine, sertraline and citalopram; previous SNRIs included venlafaxine and duloxetine.1

¶ Minimal clinically important difference was calculated to be 20 points for the ODQ-26 after 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment.3 With Brintellix® 10-20 mg, at week 8 a decrease of -29.8 points was achieved.1

§ Patients with MDD were asked the gold standard standardised screening question on emotional blunting (yes/no) developed by Price J et al. 2012 at week 8. Emotional effects vary, but may include, for example, feeling emotionally numbed or blunted in some way; lacking positive emotions or negative emotions; feeling detached from the world around you; or just not caring about things that you used to care about. Have you experienced such emotional effects during the last 6 weeks? . At baseline, all patients had to

report “Yes to this screening question.1

Abbreviations:

MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; ODQ, Oxford depression questionnaire; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

† As measured by ODQ, an effective self-report measure of the symptoms of emotional blunting in patients with depression.2

‡ Partial response defined by the investigators clinical judgement of symptom severity and type to an SSRI or SNRI monotherapy at approved doses for at least 6 weeks before the screening visit. Previous SSRIs included escitalopram, paroxetine, sertraline and citalopram; previous SNRIs included venlafaxine and duloxetine.1

¶ Minimal clinically important difference was calculated to be 20 points for the ODQ-26 after 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment.3 With Brintellix® 10-20 mg, at week 8 a decrease of -29.8 points was achieved.1

§ Patients with MDD were asked the gold standard standardised screening question on emotional blunting (yes/no) developed by Price J et al. 2012 at week 8. Emotional effects vary, but may include, for example, feeling emotionally numbed or blunted in some way; lacking positive emotions or negative emotions; feeling detached from the world around you; or just not caring about things that you used to care about. Have you experienced such emotional effects during the last 6 weeks? . At baseline, all patients had to

report “Yes to this screening question.1

Abbreviations:

MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; ODQ, Oxford depression questionnaire; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.