Stroke is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity among adult population worldwide. The neuropsychiatric disorders associated with stroke includes depression, anxiety, apathy, cognitive disorder, mania, psychosis, catastrophic reactions and fatigue. Poststroke depression (PSD) is one of the commonest emotional disorders affecting stroke sufferers

Stroke is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity among adult population worldwide. There are numerous complications of stroke including cerebral edema, seizures, deep vein thrombosis, bed sores, pneumonia, urinary tract infection and neuropsychiatric disorders.1 The neuropsychiatric disorders associated with stroke includes depression, anxiety, apathy, cognitive disorder, mania, psychosis, catastrophic reactions and fatigue. Poststroke depression (PSD) is one of the commonest emotional disorders affecting stroke sufferers. Although poststroke depression has been a recognized complication, this condition is underrecognized and overlooked. The risk of all depressive disorders was reported ranging from 25% to 79% among people suffering from a stroke.2 Moreover, poststroke depression has a great burden on functional recovery and long-term outcomes, thus a higher mortality rate. PSD affects patient’s activities of daily living, cognitive function and social functioning. More researches are needed to determine the association between poststroke depression and stroke recurrence.3 Early and effective treatment of PSD will have a positive effect on the depressive symptoms and the rehabilitation outcome of the stroke patient.

Early recognition of the diagnosis of PSD is important to ensure early treatment thus positive outcome on functional and psychosocial aspect. Depressive symptoms after stroke remains underdiagnosed, as healthcare professionals may focus on patient’s motor and functional aspects of the stroke, neglecting the psychosocial aspect.

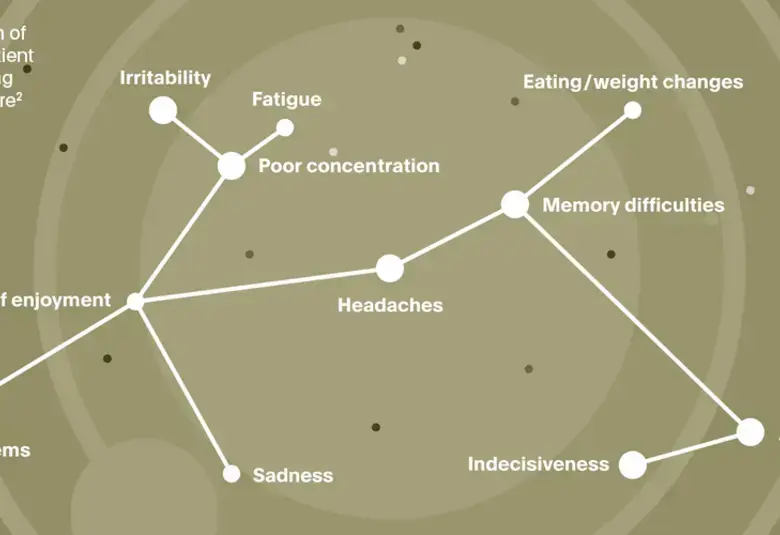

Early recognition of the diagnosis of PSD is important to ensure early treatment thus positive outcome on functional and psychosocial aspect. Depressive symptoms after stroke remains underdiagnosed, as healthcare professionals may focus on patient’s motor and functional aspects of the stroke, neglecting the psychosocial aspect. In addition, cognitive impairments such as aphasia, agnosia, apraxia and memory issues may hinder patient’s capacity to express the depressive symptom. Stroke itself may cause lack of energy, insomnia, loss of appetite, loss of concentration and psychomotor retardation which are also symptoms of depression, making the diagnosis challenging.

The diagnosis of PSD relies on the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fifth Edition (DSM-V) which defines poststroke depression as prominent and persistent period of depressed mood or markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all or almost all activities lasting 2 or more weeks.4 Patients with a diagnosis of mood disorder due to stroke with depressive features must have low mood or loss of interest or pleasure along with at least two but less than five symptoms of major depression.

There are many self-report tests in the screening and monitoring of PSD. Among those are Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) 5, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) 6 and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) 7. BDI is simple, relatively fast and requires no training to administer. The HDRS has the advantage of diagnosing depression in patients with cognitive impairment.8

The evaluation and diagnosis of PSD should be based on the subjective history from the patient and family, supported by objective depression scales. Once diagnosed, treatment should be initiated as soon as possible, and symptoms monitored closely.Although the exact mechanism of PSD is not known and very complex, there are several hypothesis. One of those include the depletion of monoaminergic amines occurring after stroke that may play an important role.9 The norepinephrinergic and serotoninergic pathways are disrupted in basal ganglia and frontal lobe lesions. Serotonergic input arising from the dorsal and caudal raphe nuclei to the hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, striatum, brainstem and neocortex, areas involved to mediate depression.

The Sydney Stroke Study suggested that amygdala, that has important role in processing emotions and cognitive function is smaller in stroke/transient ischemic attack patients and therefore may increase the vulnerability to depression

The risk factors of PSD include genetic factors, age, gender, medical and psychiatric history, type and severity of stroke, lesion location, degree of disability, and social support. Interestingly, left hemispheric lesions are more common to cause PSD, possibly as a result of involvement of left frontal, dorsolateral cortical and basal ganglia regions.10 The Sydney Stroke Study 11 suggested that amygdala, that has important role in processing emotions and cognitive function is smaller in stroke/transient ischemic attack patients and therefore may increase the vulnerability to depression. White matter lesions caused by lacunar infarcts or leukoariosis has been associated with PSD. In addition, lacunar infarcts within the thalamus and basal ganglia has higher risk of PSD. Lobar microhemorrhage has been associated with PSD. PSD seems to be more common with certain genetic variability eg. expression of the short allele of the serotonin transporter gene promoter region (5-HTTLPR). Clinical depression after stroke could be an organic consequence of the brain damage or the psychological reaction to motor disability. Degree of disability and social support such as loss of function and independence in activities of daily living, social isolation, poor self-esteem, feelings of frustration, loss of employment and subsequent financial difficulties are factors that contribute to the development of PSD. Therefore, early screening and diagnosis of depressed mood might be relevant, since depression after stroke is related to poorer outcomes.

PSD usually develops within the first few months after stroke. In a study by A. Berg et al, 46% of those who were depressive during the first 2 months were also depressive at 12 and/or 18 months while only 12% of patients were depressive for the first time at 12 or 18 months.

PSD usually develops within the first few months after stroke. In a study by A. Berg et al, 46% of those who were depressive during the first 2 months were also depressive at 12 and/or 18 months while only 12% of patients were depressive for the first time at 12 or 18 months.12 PSD may increase functional dependency and delay rehabilitation. Moreover, PSD has an association with higher mortality at 1 year after stroke and thereafter.13 Treatment of PSD will have positive effects on functional recovery. PSD may increase the risk of hypertension, diabetic complications and ischemic heart disease.14-16. The pathophysiology behind these may be partly contributed by increased platelet aggregation, carotid atherosclerosis and imbalance autonomic tone. The risk of suicide increases in stroke patients and PSD may further increase the risk. Stroke creates a high burden to the caregivers of patients and with PSD, the impact worsens.

PSD is a condition that should be treated as soon as possible. Anti-depressants have been proven to improve functional recovery in PSD patients.17 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants are most extensively studies as treatment for PSD. SSRIs are sage and have fewer side effects with relatively faster acting besides having anxiolytic effect. A novel multimodal antidepressant significantly reduces the severity of depressive symptoms in PSD and has positive effect on cognitive status of patients by improving neurodynamic functions and memory of subjects in the early period of ischemic stroke.18

A novel multimodal antidepressant significantly reduces the severity of depressive symptoms in PSD and has positive effect on cognitive status of patients by improving neurodynamic functions and memory of subjects in the early period of ischemic stroke

Besides pharmacological treatment, nonpharmacological interventions in PSD such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), psychotherapy and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) may benefit PSD despite lack of double-blind randomized controlled trials.

Both pharmacotherapy and non-pharmacological therapy may benefit patients with PSD. Importantly, these patients should be monitored regularly by a health professional. During follow-up, evaluation includes monitoring of response to therapy, review of potential side effects and ongoing management plans.

In Conclusion, Poststroke depression have been long recognized as a complication of stroke although it is underdiagnosed. The diagnosis of PSD remains a challenge with patients with stroke having symptoms similar to depression. Neuropsychological tests in the screening and monitoring of PSD are useful and important in the assessment of patients after stroke. Medical personnel and families of patients with stroke should recognise PSD. The pathophysiology of PSD remains unknown