Combining evidence-based psychosocial and pharmacological treatments significantly benefits the global quality of life of first episode psychosis patients when compared with standard community care. But the benefits of comprehensive, integrated management seen in the RAISE study diminish as duration of untreated psychosis increases. We can intervene to aid functional and clinical recovery after first episode psychosis, but it must be with the right treatment given at the right time.

Emphasis on feasibility, real-world settings and existing models of reimbursement

The enormous burden schizophrenia imposes on sufferers, families and society is unarguable. But there has been considerable debate on how best to reduce its impact. Research is made difficult by the multi-faceted nature of schizophrenia and its management, by the practicalities of organizing randomized trials, and by the fact that integrated care is not easy to implement in a health system, such as that in the United States, where there are a variety of providers and payers.

The RAISE (Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode) Early Treatment Program Clinical Trial is the first randomized controlled trial of multidisciplinary intervention ever conducted in multiple community settings in the USA.1 It compared a highly-developed, comprehensive care program against the community care usually offered to people with first episode psychosis. This ground-breaking study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Dr. John Kane discussed the RAISE trial for people with first episode psychosis

34 non-academic centers across 21 states in the US were involved and the trial. Based on 404 patients randomized by center, results showed that comprehensive intervention can improve the trajectory of patients with first episode psychosis in the life domains that matter most to them and their families.

The study is remarkable in having ensured scientific rigor despite the variability of real-world settings. It had the highest standards of training and supervision, ensuring that participating healthcare personnel delivered what the protocol required.

What did RAISE involve?

To convey the idea of guiding individuals through difficult terrain – through what is described as “the haze of mental illness and the maze of mental health services”2 – the comprehensive care package was termed NAVIGATE. It was made up of four core, evidence-based interventions:

- personalized medication management;

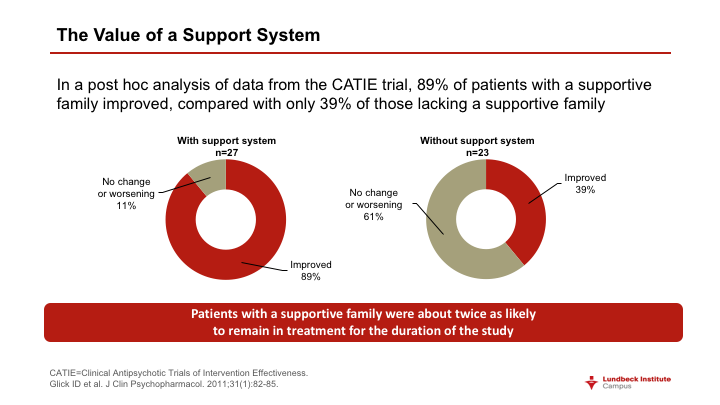

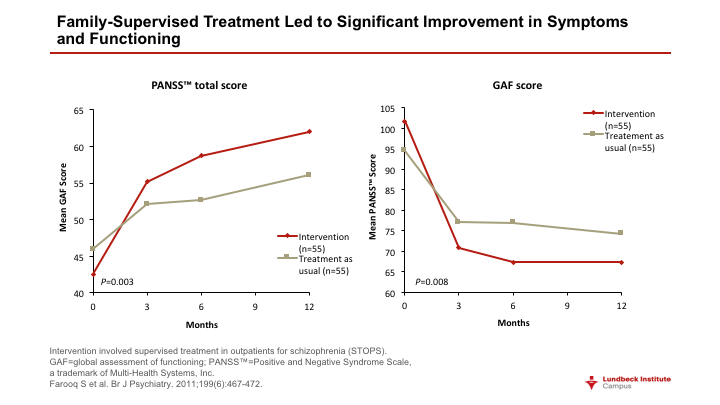

- family psycho-education;

- individual therapy focused on resilience; and

- support in employment and education

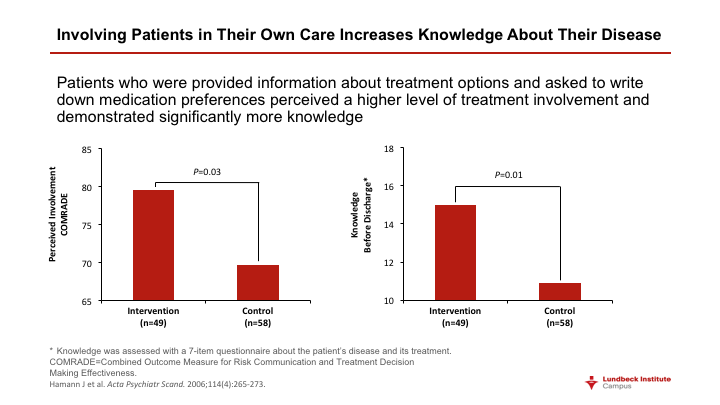

Services were coordinated by a team leader who was the main contact for patients and families. The program emphasized shared decision-making centered on the preferences of patients.

In terms of pharmacotherapy, an expert panel developed a web-based decision support system (termed COMPASS) which facilitated choice of agent (considering the fact that drugs recommended for first episode psychosis are not always the same as those used in patients who have had several psychotic episodes). There was systematic monitoring of signs, symptoms and side-effects.2 The system also facilitated direct communication about the problems patients most wanted to address and any desire they had for change of treatment.

The psychosocial interventions – family education designed to foster a collaborative relationship, and individual resiliency training – combined general modules (goal setting, education about psychosis, relapse prevention and processing the psychotic episode) with modules individualized to the patient. These included dealing with negative feelings and substance abuse, living healthy, and developing relationships.

The “NAVIGATE” package conveyed the idea of guiding people through difficult terrain towards functional health

Inclusion of the fourth key component, specialized support for employment and education, was seen as important since these aspects of life are highly valued by patients and their families and help engage them in treatment.

The control arm – community care – involved treatment for first episode psychosis determined by clinician choice and the availability of services. But all participating centers had been judged at the start to have enough clinical and administrative resources to implement comprehensive care, if required by randomization.

Since intervention required the training of many staff, who would naturally share their knowledge within their place of work, randomization to experimental or control arms was by clinic. Seventeen clinics were assigned to each condition.

Two-year results RAISE the bar

Quality of life (QoL), the primary outcome of this landmark study, was measured by centralized physician assessors (who were blinded to the treatment received) using the Heinrichs-Carpenter scale during a live, two-way video interview. The scale used includes sense of purpose, motivation, emotional and social interactions, role functioning and engagement in regular activities.

At two years, QoL had improved significantly more among people given comprehensive care than in those receiving standard community management. The effect size of 0.31 was judged to represent a clinically meaningful difference.

Patients in the integrated intervention group were also significantly more likely than controls to be in work, school or college. They were more likely to have remained in treatment: those who had the package of interventions stayed a median of 23 months, compared with 17 months for those in the control group. And patients receiving the NAVIGATE package showed significantly greater symptom relief according to their total score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and their score on the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

Coordinated care can be given in a wide range of community settings and improves the quality of life of first episode psychosis patients. But early intervention is essential.

One of the principles underlying NAVIGATE was that the program should provide support for clients’ personal autonomy. So it is worth noting that those in the intervention arm did perceive significantly greater support for their autonomy over the course of treatment, while those receiving standard community care did not.3

Comprehensive care did not reduce rate of hospitalization for psychiatric indications, which was 34% in the NAVIGATE group and 37% among controls. But it should be noted that rates in both arms of the study are relatively low for first episode psychosis and reflect well on the centers randomized to the control arm. The fact that they were interested in participating in the study shows that all centers – including those subsequently allocated to providing customary community care – were highly motivated to achieve the best outcome for their patients.

Medication was individualized to reduce side effects and adverse outcomes for physical health

The mean age of patients in both arms of the study was 23 years (range 15-40 years). The majority were male (78% in the comprehensive intervention group and 66% of controls); and the great majority (89% of NAVIGATE patients and 90% of controls) had a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis. A criterion for entry to the study was that patients had had a lifetime exposure to antipsychotic treatment of six months or less. The mean duration of prior antipsychotic use in both NAVIGATE and control groups was a little over 40 days.

Early intervention means early

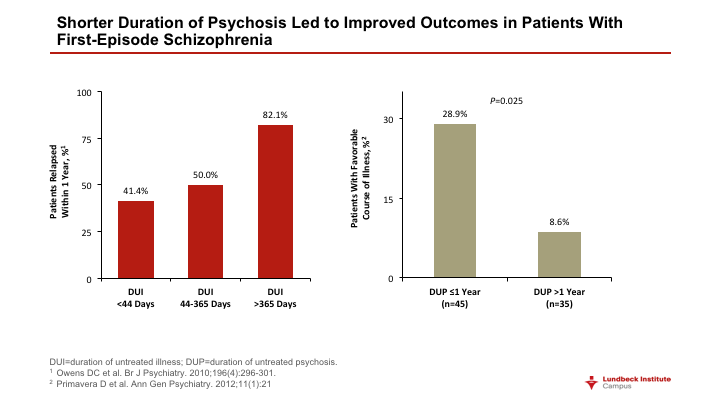

Remarkably, the median duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) for patients enrolled in the trial – defined as the time between onset of psychotic symptoms and the start of drug treatment -- was 74 weeks. The fact that the trial design did not place limits on DUP led to a finding with profound implications for our understanding of the importance of timely intervention.

Findings have profound implications for timely intervention

The effect size of integrated care on QoL was 0.54 for patients with a DUP of less than the 74-week median and 0.31 for the study population as a whole. The integrated care program led to a robust improvement in outcome in patients for whom intervention was achieved relatively early, but had less effect after 74 weeks.

The outcome of RAISE clearly supports the philosophy of integrated treatment. Choice of quality of life as the primary endpoint was crucial since functioning in the community and at work and having meaningful relationships are the outcomes most valued by patients.

Rapid referral is an essential aspect of effective care. The study is a landmark piece of research in that it illustrates – so clearly – the negative impact of a prolonged DUP. The authors of the pivotal paper describing the two-year outcome of RAISE argue that reducing DUP to less than three months is an issue of national importance.1

Results demonstrate the vital role of early detection of first episode psychosis and early engagement in integrated care

Making an appropriate diagnosis of first episode psychosis means distinguishing the condition from substance abuse or other medical problems that could account for psychotic symptoms, said Dr John Kane (principal investigator on the RAISE – Early Treatment Program). The presence of hallucinations or delusions of sufficient intensity, frequency and duration is needed to affirm a diagnosis of a psychotic condition. This is often supported by evidence of deteriorating functioning in school or work and in social relationships.

Unfortunately, people often experience a long duration of untreated psychosis, Dr Kane continued. The longer the period of undiagnosed and untreated psychosis, the more difficult it is to achieve a good outcome. In the RAISE study, if the DUP was greater than 74 weeks, there was less benefit from comprehensive intervention. Timing is important.

Evidence from RAISE shows that comprehensive and coordinated specialist care can improve the trajectory of early phase psychosis and schizophrenia, and so should be made available, he argued. Comprehensive care means that we include individual therapy, family therapy, family education – along with supportive employment and education.

The team-based approach was also key to RAISE. Family and individual therapists worked together. Dr Kane noted that they discussed information and challenges; and worked with each other and the patient. The program was tailored to meet the specific needs and goals of the individual patient and family. We can help them deal with the fact that they have experienced the onset of a serious illness and help them achieve their goals and aspirations. We can promote optimism, while being realistic about the need for treatment. But while we can offer treatment, people need to stick with it, Dr Kane urged.

Consistent, coordinated, evidence-based care can help people return to a normal life in the community

It is also crucial that we offer help with lifestyle factors such as smoking and exercise, and with medical issues given that compared with the general population, people with chronic, severe mental illness have an expected lifespan that is about 25 years less.

The more we succeed in improving outcome, the more we will succeed in reducing the stigma of mental illness.

What of the future?

In an editorial in the American Journal of Psychiatry that accompanied publication of the two-year results from RAISE, Dr Thomas Insel (National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA) drew a parallel with the medical profession’s achievements in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).4 Over the past four decades, research has transformed prospects in ALL from an 80% mortality rate to an 80% chance of cure.

This was achieved incrementally through incorporation into standard of care of a succession of small improvements, each of which had been evaluated by rigorous clinical trial. Progress was based on individualization of therapy and multi-disciplinary endeavor. There is every reason to think that a similar process of optimization can lead to radically improved outcomes in schizophrenia. But, just as in ALL, it will require that we provide the right treatment at the right time.

On the evidence from RAISE, such treatment needs to be recovery-oriented, team-based, comprehensive and person-centered. It also needs to be available as soon as possible after first episode psychosis. With this in mind, the NIMH is developing the Early Psychosis Intervention Network, to implement the RAISE findings within the healthcare system. The initiative also aims to prevent first episode psychosis in young people at high risk.

The findings from RAISE provide a cause for concern in revealing the extent of delay in intervention. But in confirming studies in other countries (such as Denmark and the UK) showing that comprehensive intervention can be effective, they “raise a hopeful note”, Dr Insel argues. We are just at the start of a change in our expectations of recovery following first episode psychosis.