Greater clinical benefit for patients with brain disorders and gains in cost-effectiveness for society -- both can be achieved by earlier intervention, closer co-ordination of multidisciplinary care, and disseminating best practices in treatment. Parkinson’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease and schizophrenia are among the areas considered in detail by the European Brain Council’s Value of Treatment initiative.

The Value of Treatment (VoT) Project is a timely and ground-breaking initiative of the European Brain Council (EBC). It argues that optimizing interventions in mental health and neurological diseases can bring both positive outcomes for patients and socio-economic gains for society. The Project aims to support its views with robust empirical data, and to make policy recommendations from solid scientific knowledge.

Based on two years of research, the Project identifies current problems along the entire care pathway, from prevention through screening, diagnosis and treatment, to follow-up and rehabilitation – and then proposes solutions. Early detection and prompt intervention are regarded as the starting point, with greater use of evidence-based guidelines for screening.

Fundamental to treatment is the planning of coordinated, multidisciplinary, patient-centered care. Along with this goes patient education and empowerment to encourage adherence and compliance. Electronic reminder systems exemplify the potential value of e-health tools.

General policy recommendations made by the EBC are: the need to assess the impact of brain diseases on the outcome of other medical conditions; health systems evaluation so that effective interventions can be identified and then replicated in similar settings; the establishment of common research platforms (Knowledge Hubs) to share data; and the encouragement of EU-wide initiatives in brain health to promote collaboration.

Health is wealth: In Europe, the direct and indirect costs of brain disorders exceed 800 billion euros each year – more than CVD, cancer and diabetes combined

Giving the brain proper priority

The EBC recognizes the burden suffered by affected individuals, their families, friends and carers – but also by society at large. In Europe, the annual direct and indirect costs of brain disorders exceed 800 billion Euros1 – more than cardiovascular disease (CVD), cancer and diabetes combined. Yet our total research expenditure on brain disorders is smaller than the expenditure on each of these disease areas.

As we deal more effectively with CVD and even with cancer, brain diseases come to the fore. Society has not yet caught up with this fact, but Professor David Nutt, chair of the EBC, along with the other members of the Council, are determined that it should.

Prof David Nutt - Value of Treatment

Prof David Nutt - Value of Treatment

In brain disorders, we need a paradigm shift towards value-based healthcare interventions

We have to educate people that a healthy brain is critical to a healthy body. As the Roman poet Juvenal wrote: Mens sana in corpore sano.

The VoT Project aimed to gather evidence to help us deal more effectively with brain disorders. The answer is to maximize the value of the treatments we already have, and to use our knowledge to develop the treatments of the future. We do have good treatments, but they are not being adequately used, Professor Nutt believes. In part, this is due to an overall lack of coordination and integration. Research shows us that the earlier we can diagnose a condition, the earlier we can intervene leading to better outcomes for patients and their loved ones.

The Project covered a range of neurological conditions including epilepsy, stroke, the dementias and Parkinson’s Disease and – in the realm of psychiatric health – schizophrenia. Many of its policy conclusions relate to brain disorders as a whole.

A comprehensive approach

With brain disorders in general,

- primary prevention is the ultimate goal

- in the absence of prevention, time matters: early intervention – including intervention in the prodromal phase -- results in objective gains in survival, reduced disability and improved quality of life, and lower overall treatment costs

- early intervention and the integration of healthcare are central to delivering sustainable models of management that provide good value in our use of limited resources under conditions of economic constraint

- although there are no curative treatments, technological innovation is moving at an unprecedented pace; and we struggle to adapt quickly enough to maximize the benefits to patients and society

- progress requires clear procedures for referral from primary to secondary and tertiary care and implementation of evidence-based guidelines

- patients’ needs embrace medical, psychological and social domains; and cognitive, educational and vocational concerns are common denominators that link many brain disorders.

The brain is the source of intellect, emotion and behavior; a source both of the person and of their participation in society.

The ECB’s VoT initiative adopted a bottom-up approach, starting with analysis of case studies and building towards policy recommendations. It assessed treatment gaps, and the cost of non-treatment or inadequate treatment. In this feature, we focus on its findings in relation to Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Parkinson’s Disease (PD) and schizophrenia. You can read the full VoT report on EBC webpage.

Alzheimer’s Disease: the search for disease-modifying treatments

In Europe alone, there are currently over 10 million people with dementia.2 As a result of an ageing population, the burden of dementias – notably AD, which is by far the most frequent cause – is increasing. While there are symptomatic treatments, nothing yet has been shown to alter the natural history of the disease. However, the long prodrome offers potential opportunities for primary prevention.

Biomarkers are likely to have a positive impact on screening, diagnosis and the management of AD. Our ability to identify people with subjective cognitive decline or mild cognitive impairment (MCI), for example, should allow us to explore early intervention using disease-modifying agents to prevent or slow disease progression.

The ability to identify people with prodromal or pre-clinical dementia who have the highest likelihood of progression may allow us to delay the onset of clinically significant disease and extend their ability to live at home, delaying the need for institutional care.

Disease-modifying approaches are now being assessed in people who are asymptomatic but judged to be at high risk of developing AD on the basis of their genetic profile, results from PET imaging, or assessment of biomarkers.

Optimizing interventions in mental health and neurological diseases can bring both positive outcomes for patients and socio-economic gains for society

Potential economic impact of altering the natural history of AD

The greatest costs in managing AD arise from i) the need for the long-term institutional care of people who cannot live in the community, and ii) the burden on informal caregivers looking after those who can. Both these elements were included by Handels and colleagues in a model that assessed the impact of a hypothetical disease-modifying treatment in a virtual cohort of 10,000 people with normal cognition or MCI who tested positive for amyloid beta.3 It was assumed that the hypothetical agent would reduce progression to dementia by 50%.

Compared with usual care, the disease-modifying treatment would increase the length of time people spent with normal cognition or MCI, and increase life expectancy (since mortality is lower in pre-dementia states) (Fig 1). As a result, the number of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were higher over time (Fig 2).3 Since active treatment resulted in slower progression, healthcare costs were also reduced when compared with current care.

Parkinson’s Disease: improving outcomes

Parkinson’s Disease (PD) affects around 10 million people across the globe.4 Due to an increasingly aging global population, the number of people suffering from PD is expected to double over the next twenty years. In Europe alone, the cost of treating PD in 2010 amounted to almost 14 billion Euros;1 costs which are expected to continue increasing.

Of the neurodegenerative diseases, it is second in frequency only to AD. Despite being well-known, the diagnosis of PD is problematic since there is a diverse range of symptoms; symptoms which often overlap with other diseases. For these reasons, definitive diagnosis is often delayed. More research is required to clarify the prodromal stages of PD, with a view to conducting trials examining potentially neuroprotective agents.

More research is required to clarify the prodromal stages of PD, with a view to conducting trials of potentially neuroprotective agents

At the moment, we have no reliable PD-related biomarkers, however, increasing evidence suggests that hyposmia and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder precede the development of even subtle motor symptoms. Further, potential exists for skin biopsies to detect aggregates of phospho-alpha-synuclein in people who are asymptomatic but at high risk, and imaging studies may prove helpful. Certain gene mutations which enhance risk of the disease have also been identified.

In established PD, optimizing pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments can reduce symptoms from early- through to late-stage disease. This requires that care is tailored to the needs of the individual patient. At present, however, there is often a lack of coordinated care and shared decision-making; and a major problem of non-adherence to treatment, leading to unnecessary motor dysfunction. This can be improved by involving patients in treatment decisions, providing more information to patients and carers, attending to side effects, and personalizing care.

Health economic assessments

Three major deficiencies in management of PD with available treatment were identified in the VoT Project: the lack of early/timely treatment; lack of adequate treatment for advanced disease (Fig 3); and poor adherence with treatment. Tinelli et al conducted economic analyses assessing the cost-effectiveness gains that could be achieved if each of these deficiencies was addressed by new treatments.5

The first analysis investigated a hypothetical intervention that could improve patients by one grade on the Hoehn and Yahr severity scale. Cost savings and quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gains – in comparison with no treatment – were seen over one year, regardless of baseline patient disease severity.

A second analysis showed that making adequate treatment available to more PD patients is also cost-effective, since increased costs are accompanied by an increase in QALYs.

Further analysis suggested that improving adherence to treatment would result in substantial cost savings – derived mostly from reduced use of hospitals and nursing homes. In the German healthcare system, the potential annual savings were 0.25 to 0.5 million Euros, and in the UK between 1 and 3 million Euros.

Making adequate treatment available to more PD patients is cost-effective since increased costs are accompanied by an increase in QALYs

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is severe, potentially disabling, and a major cause of lost healthy life years and diminished quality of life. Worldwide, it is among the top 25 causes of disability.6 The time of onset is typically between the ages of 18 and 35 years. The disease affects around 1% of the adult population and typically presents as a crisis, suggesting that opportunities for earlier intervention have been missed. This is due to a combination of factors including lack of disease awareness among patients, family, and the community; stigma related to the disease; lack of training among the providers of primary healthcare; and limited opportunities for referral to more specialized services.

In addition to the morbidity caused by the mental illness itself, people with schizophrenia are at far greater risk than others of premature death due to diseases such as diabetes, hypertension and CVD. Compared with non-affected people, those with schizophrenia have a life expectancy that is reduced by up to thirty years. There is increased risk of suicide, but a large part of the excess is due to comorbid conditions. Some of this is attributable to lifestyle factors, and some to the adverse metabolic effects of certain treatments.

Ways of improving management

The development of acute psychosis and schizophrenia are generally preceded by a prodromal phase. This offers opportunities for intervention to reduce the effects of risk factors such as anxiety, depression and substance abuse (Fig 4).7 In people known from their family history to be at high risk of developing schizophrenia, there are even earlier opportunities for psychosocial interventions to encourage resilience and subsequently reduce susceptibility to what can be a devastating disease.

Each relapse in schizophrenia contributes to neurobiological impairment and reduces the likelihood of good long-term functional outcome

Though many people with acute psychosis respond to drug treatment, relapse due to poor treatment adherence is common. This is partly due to disease-related lack of insight, but the inadequate provision of information about side-effects and their management is a major contributory factor. Even so, around half of all patients have a reasonably good long-term outcome in terms of control of symptoms and restoration of pre-morbid functioning.

As with many brain disorders, severity and chronicity are adverse factors. Each relapse in schizophrenia contributes to neurobiological impairment and reduces the likelihood of quality, long-term functional outcomes. It is estimated that around half of all people with schizophrenia do not receive adequate and timely treatment.

Based on evidence of improved outcome, there is increasing enthusiasm for early intervention that integrates pharmacological and psychosocial treatments. The longer schizophrenia remains untreated, the more the personal and economic benefits of comprehensive treatment and support diminish.

Evaluating early intervention

The EBC VoT Project assessed the economic value of early intervention in schizophrenia, ie intervention in the prodromal phase and early in first episode psychosis. The study compared the UK, where such intervention is available (and largely community-based), with the Czech Republic, where it is not.8 (Figs 6-10) This evaluation took into account not only the healthcare costs of early intervention but also the costs arising from in-patient hospital stay, unemployment and lost productivity, involvement in the criminal justice system, and need for housing.

Using the UK early intervention approach, the evaluation suggested that overall medium term cost (over 2-5 years) was likely to be 20m Euros less and long terms costs (beyond five years) were projected to be 32m Euros lower. This is despite the fact that early intervention using the UK model was more costly than usual care over the first one to two years, due to additional spending on healthcare (additional cost was estimated at 39m Euros). Long-term reduced costs were attributable to reduced needs for inpatient care, less involvement with the criminal justice system (including prevention of homicide), and improved opportunities for employment. These estimates were robust in sensitivity analyses assuming a range of probabilities relating to employment and involvement in crime.

The EBC report estimates that if the Czech Republic adopted both prevention and early intervention policies, the costs of managing schizophrenia could be reduced by up to 40% compared with usual practice based largely on in-patient treatment costs. The study calculated that the annual cost of care for the 5,500 people developing first episode psychosis is currently 46m Euros (translating to approximately 8400 Euros per patient). Adopting and implementing a comprehensive prevention and early intervention approach, however, has the capacity to save more than 3000 Euros per patient, illustrating the importance of early recognition and intervention.

Medium and long-term costs were lower due to reduced needs for inpatient care, less involvement with the criminal justice system, and improved opportunities for employment

The broader picture: general recommendations

While the Czech Republic provided a specific example for economic analysis, the overall conclusions from the EBC’s assessment of schizophrenia management have wider applications. Care pathway analysis using focus group sessions, interviews with experts and literature review identified major treatment gaps and unmet needs in relation to: missed opportunities for early detection and diagnosis; limited access to effective treatment; non-adherence with treatment; lack of rehabilitation programs; provision of care in the community and prevention of relapse.5

Efforts to improve care and reduce the personal, social and economic burden should focus on:

- increased community awareness and understanding of schizophrenia through provision of information and support to patients, family and formal and informal carers

- maintenance of well-being in those at high risk of psychosis or in a prodromal phase

- reduction in the stigma that adds to disease burden and discourages early disclosure of psychotic symptoms

- provision of services that allow early detection and intervention and their integration into systems offering comprehensive care; wherever possible these services should be provided in the community rather than in institutions

- restoration of function and quality of life: efforts are needed to rehabilitate patients and encourage re-integration into the worlds of education, work and wider society; this involves a wide range of health and social care professionals

- monitoring the patient and prevention of relapse, which in many cases is due to non-adherence with treatment.

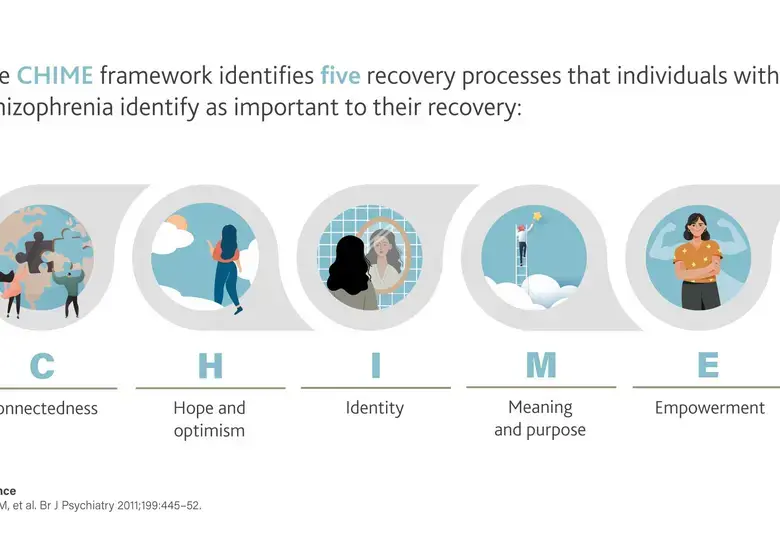

Among current barriers to optimal management identified by the VoT Project were lack of coordination between health and social care professionals; lack of continuity in treatment with antipsychotics; poor availability of programs designed to counter cognitive and social impairment and promote re-integration; and lack of collaboration between carers and families in setting and achieving goals. There is also a need for a shift in the care paradigm from control of symptoms to achieving functional recovery.